I had an early flight, so I went to bed long before I was tired. But it doesn’t matter—I never sleep when I know an alarm will wake me before sunrise. I just lie awake, my thoughts and I in a minuet of worry, until the bell tolls. That night was no different.

Five hours passed. Cars drove by, coyotes howled. I dressed for imaginary occasions in my mind. I thought of my mother, a lifelong insomniac happy to scrape by on three or fours hours a night. I felt heavy and conspicuous, like a fallen statue.

When the alarm finally rang I rose, dressed, and gathered my things. Just as I was making coffee my phone pinged: the airline. My flight was four hours delayed. I went back to bed—still exhausted, now fully dressed. Again, I lay there, wide awake. I was about to give up when I was pulled out from under the sheets by my ankles.

In a single motion, an unknown force tossed me like a ragdoll out of the sliding-glass door. Voices echoed and called across the horizon as I tumbled through the sky, in a constellation of blue pinpoint stars that were also me. I realized I was dreaming.

It wasn’t like any dream I’d ever experienced: I was completely awake, and, once the panic subsided, I realized, in control. I concentrated, tried barrel rolls. I felt the pillow close; felt the reality of my bedroom just beneath the dream. The bed pulled me back, the force pulled me out again. I dove, coasted, watched the sun rise over the skyline of LA. I wondered if I might miss my flight.

There is, of course, a robust community of lucid dreamers on Reddit. On their recommendation, I picked up Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming, a 1990 manual by the Stanford psychophysiologist Stephen LeBerge. The book outlines a technique for becoming reliably lucid: MILD, or the Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreams (a more advanced technique, WILD, can cause night terrors if done incorrectly).

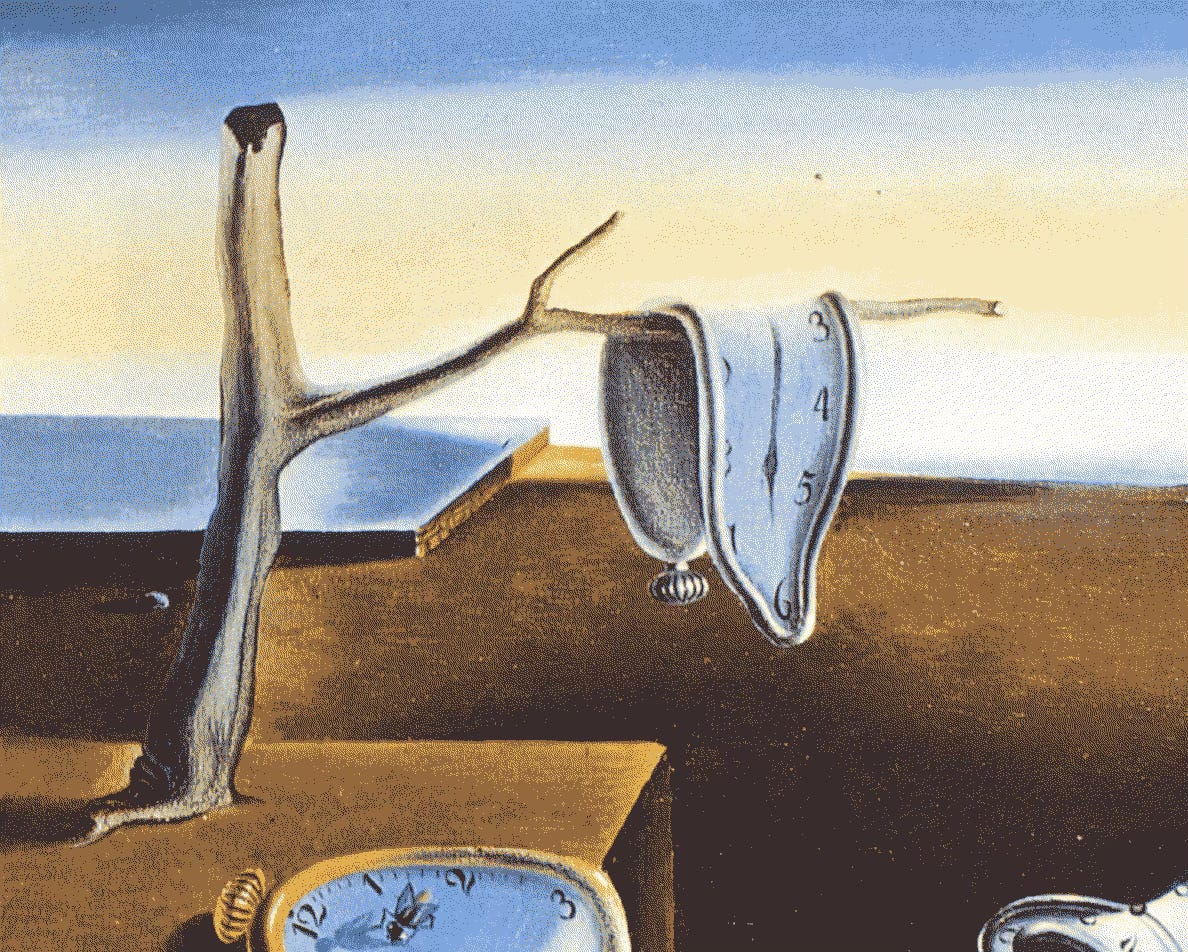

One of the fundamentals of lucid dream induction is something LeBerge calls “critical state-testing technique.” The Reddit community calls it reality testing. It’s simple: every day, as often as possible, perhaps every time you pass through a door, ask yourself if what you are experiencing is real. Ask yourself seriously. Look around and justify your answer. Count your fingers. Plug your nose. Look at your watch, then look again to see if the numbers are still there. Try to pass your hand through your palm. Do this often enough, and it becomes a habit. Eventually you’ll do it in your sleep. And when that happens, you will find that your fingers multiply. You can breathe with your nose plugged. The watch is unreadable. Dream Standard Time: you’re asleep.

LeBerge writes that the dream world is as “real” as its waking equivalent, at least in a sensory sense. To our brains, the sights and sounds of a dream are as real as any other experience. The difference is that while objects in the waking world exist outside of our perception of them—persisting even when we’re not looking—dream-objects are created anew in each moment of perception. I found this idea eerily reminiscent of the great science fiction writer Philip K. Dick’s one-sentence definition of reality:

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

This definition, to which I probably refer too much, is from “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” a meandering speech Dick gave in 1978. It’s pure Dick: observations about Disneyland, nods to pre-Socratic philosophy, stories about androids that don’t know they’re androids, an account of Dick’s prophetic visionary experience, and a deep dive on the theory, developed from that experience, that we live in an ancient world, reality is an illusion, and time is accelerating.

In the speech, he talks about having an extraordinarily vivid dream, which he felt compelled to put to paper, and which figures as a scene in his 1974 novel Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said. After the book was published, he realized the scene was from the Bible. His conclusion was that both the Bible and his novel drew from the same well of truth, the same observation of a real world that persists beneath the collective dream of waking life.

“An author of a work supposed fiction might write the truth and not know it,” he said.

Finally, here are some recent long-form pieces from me, which I wrote—as best as I can tell, anyway—in a fully-conscious state:

The Perpetual Zoom, for Grow Magazine

I began this piece on the history of microscopes nearly a year ago, when a casual interest in the Dutch microscopist Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek turned into a mild obsession. Leeuwenhoek was a self-taught draper from Delft and the first human to see beyond the visible, peering through a tiny bead of glass into the world of bacteria, which he called “animalcules.” Writing this piece, I was trying to get at what it really means to “see” through a microscope, and how modern microscopy techniques—using electron beams, lasers, and scanning probes to plumb data from the microrealms—push our understanding of “seeing” to the point of total abstraction. Shoutout to the UCLA NanoSystems Institute, who were generous enough to let me look at all their advanced microscopes, and to the ladybug who landed on my foot while I was there.

The New Mechanical Turks, for PioneerWorks

This is a conversation with the writer Joanne McNeil about “fauxtomation:” when tech companies obfuscate the human labor powering allegedly automated content moderation systems, food delivery robots, and self-driving cars. McNeil’s very good debut novel, Wrong Way, out now with MCD Books, is about the hidden life of one such worker, the driver of a “driverless” car. It’s sci-fi, but, reading it, I couldn’t help but think of Philip K. Dick’s observation: that a writer of supposed fiction might inadvertently chance on the truth. This conversation is the second installment in Three-Way Mirror, a series of long-form conversations about AI I’m publishing with PioneerWorks. The first, if you missed it, was with the Canadian novelist Sheila Heti.

Finally, a bit of news! I received word this week that I’ve been awarded a 2024 MacDowell Fellowship. So I’m excited to announce that I will be spending some time next year in a cabin in the forest—working, finally, on my next book.

Sleep well,

Claire