After seven hours in the car, the road still pulls like a tide on my ears. Even after I’m splayed on the motel bed, its momentum continues, as though the tarmac were unspooling somewhere below the box spring. Fitting, then, that the movie we’ve selected from the depths of the cable box is about the liquid pull of the world.

Aaron Eckhart discovers that the molten metal core of the Earth has stopped spinning, sending the electromagnetic field into chaos and exposing patches of the planet to the raw sun. Rome burns; fish boil alive in the San Francisco Bay; migratory birds lose the plot, as do I; faulty navigation systems force Hilary Swank to land a Space Shuttle in the LA River. The only solution is, of course, to nuke the Earth’s core, a mission Eckhart and Swank undertake post-haste, riding a blind heatproof bullet straight through miles of CGI magma. At every interval the commercial breaks grow longer. They advertise glistening tri-patty burgers and increasingly specific pharmaceuticals addressing rare cancers and skin conditions. Regional ads for the local power utility beg for moderation in the summer heat, and when the movie returns, Eckhart is deeper within the scorching Earth and even more shirtless.

On its release in 2003, The Core was pilloried by critics and cited by the scientific community as an example of everything Hollywood does wrong in its representation of science onscreen. In a poll, hundreds of scientists voted The Core the worst offender in recent memory, and Dustin Hoffmann, at the time the ceremonial face of the Science and Entertainment Exchange, lobbied for its thorough debunking. The Core’s writer, John Rogers, was forced to respond that he did his best, that he’d even fought with the studios to excise even more egregious pseudoscience: spacewalks in liquid magma, subterranean dinosaurs, and a windshield for the film’s tunneling ship, Virgil.

In Rogers’ defense, a scientifically accurate version of The Core (or The Journey to the Center of the Earth, for that matter) wouldn’t have been very exciting to watch. The Kola Superdeep Borehole, the deepest hole ever drilled into the real Earth, only penetrated a third of the way through the continental crust somewhere just shy of the Finnish border. That’s a little under eight miles; the Earth’s core, for reference, is 4,000 miles deep. Although it surfaced plenty of surprises from deep below the permafrost—boiling hydrogen-rich mud, a shock of liquid water, and even microscopic Plankton fossils as far as three miles below the surface—it was hardly the stuff of adventure tales.

Even before the Russians welded it shut in the ‘90s, the Kola Superdeep Borehole was only 9 inches wide, and in photos, its opening peters immediately away into darkness, a blank slate that has been enthusiastically filled in by eldritch creepypasta authors, clickbait farms, and evangelical memelords suggesting that the Soviet Union opened the gates to hell. Images taken by urban explorers of the abandoned site could not look more like outtakes from Stalker, adding to its postlapsarian Soviet spook factor.

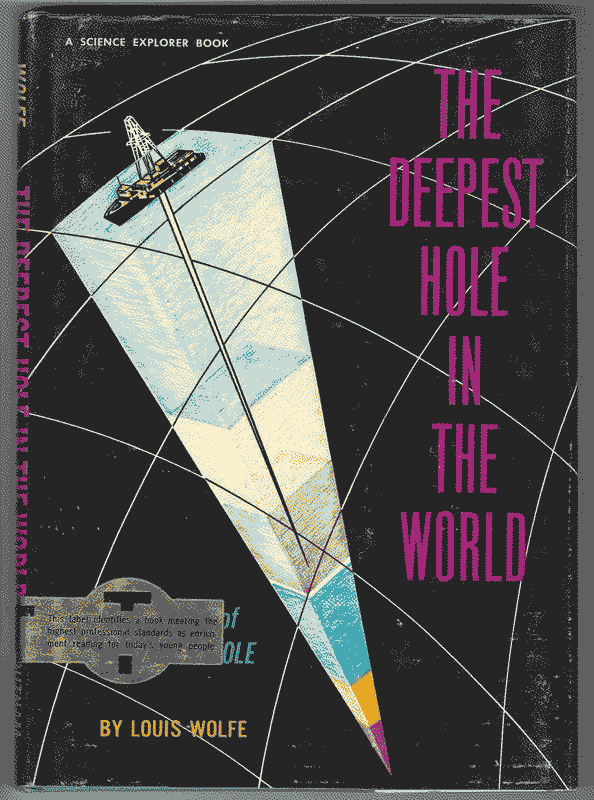

The Kola Superdeep Borehole is the forgotten ruin of a lesser-known Cold War rivalry between world powers. As the US and Soviet space programs plotted their paths to the moon, an inner space race was on, too—to plumb the deepest point on Earth. The US made its attempt at sea, where the crust is thinner, off the coast of Guadalupe, Mexico. Project Mohole, named for the Mohorovičić discontinuity, a magma-filled layer separating the Earth’s crust from its mantle, didn’t make it very far before it hit cost overruns and political infighting, but the engineers on the project did invent the “dynamic positioning” systems required to keep a drill steady at sea, opening the gates to a very different kind of hell: the proliferation of deep offshore oil drilling.

This was likely the objective from the get-go. Project Mohole’s drilling barge, the CUSS I, was funded by a consortium of oil companies: Continental, Union, Superior, and Shell. John Steinbeck, who sailed on the CUSS I to cover it for LIFE Magazine in 1961, wrote as lustily as you might expect of the “elite and motley” group of paleontologists, oceanographers, and petrologists aboard. The latter were “the cream of a very special profession already trained in offshore drilling in shallow water.” As the drill plunged through the mud, none slept, none showered; when it finally hit pay dirt, that cream grubbed for hunks of crystal-flecked basalt to take home.

The Europeans dug a superdeep hole, too, albeit much later: the Kontinentales Tiefbohrprogramm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (KTB) Borehole in Bavaria broke ground in 1987 and made it just under six miles, recording temperatures of more than 500°F at its deepest point. Unlike the Soviet hole, the KTB is still open to researchers, tourists, and even the occasional artist-in-residence. In 2010, the Dutch artist Lotte Geevan made geophone recordings of the rumbling sound emanating from deep within the KTB, which she said made her feel “very small.”

Although both make us feel very small, the challenges of inner-space exploration are, in every way, inverse to those presented by outer-space travel: tremendous pressure and heat make it impossible to dig beyond a certain point. The mantle is yet to be breached; pending some miraculous advance in materials science, it’s unlikely that it ever will. In The Core, a geophysicist named Brazz, played by Delroy Lindo, has to invent a “37-syllable-long tungsten titanium crystal alloy” called Unobtanium to render the ship impermeable to the molten Earth. Conveniently, it also draws power from heat, a late-blooming fact that keeps our heroes from roasting to death in the center of the world. They retrace their long road, riding a lava flow to surface from within an ocean volcano off the coast of Hawaii. Whales circle and sing; Deep Earth Mission Control toss off their headsets in relief; the skies calm their freak; the planet turns another day. Tomorrow we drive on.

In other news: next week, the German writer Theresia Enzensberger and I will be having a public conversation at the Goethe-Institut in Los Angeles. Theresia’s most recent book, Auf See (At Sea), about a failed libertarian seasteading commune, was nominated for the German Book Prize; I had a chance to read some of the work-in-progress translation and it’s exactly the kind of cutting near-future critical sci-fi I love. We’re calling the event "Slime Molds and Seasteads;” our conversation, moderated by Sherryl Vint, director of the Speculative Fiction and Cultures of Science program at UC Riverside, will be wide-ranging, weird, and certainly of interest to readers of this Substack. It’s free, the parking is free, and we’ll have algae cocktails.

xo

Claire