Happy New Year, everyone. I write this brief reflection to you from my in-laws’ home in Vaasa, Finland. This close to the Arctic circle, the sun rises a little past ten in the morning and moves low across the sky, never quite clearing the birch forest on the horizon. At midday it’s already setting and by three in the afternoon it’s night again. While present, the sun is fiercely golden. Everyone takes advantage. Cross-country skiers and dog-walkers appear on the frozen lake, and a neighborhood teen, I’m told, with a sizable TikTok following, whips donuts on a hot-rod snowmobile. Light here is a precious commodity. But then it is everywhere, especially these days.

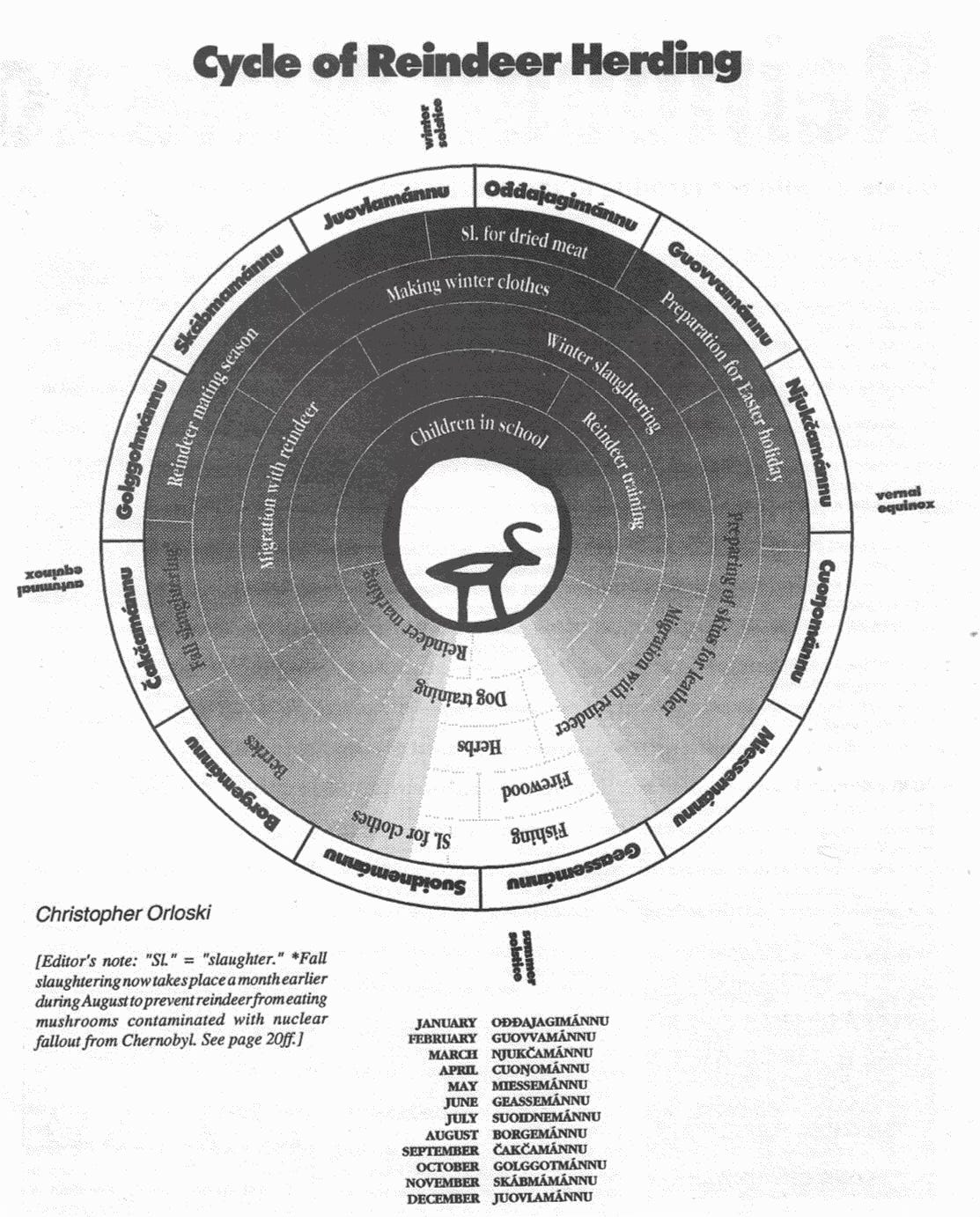

In the sleeplessness of my intense jetlag I’ve been reading about the Sámi people, indigenous to the Sápmi territory spanning Northern Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. Their calendar has eight seasons (including spring-winter, pre-summer, pre-autumn, and pre-winter) and twelve months, articulating successive changes in the environment and its inhabitants. March is Njukčamánnu, Swan Month; April is Cuoŋománnu, Snow-Crust Month; May is Miessemánnu, Reindeer-Calf Month. When these months land—on which precise days—is less important than their sequence: Swan before Snow-Crust, Snow-Crust before Calf, Calf before Hay, Molt and Rut, all of which fall before Dark-Period, which begins in Skábmamánnu, or November.

In the colonial calendar, March is March, but the thin crust of ice over the snow and the Whooper Swans appear when they appear, on nature’s time. This means March is fluid, and it can change, for better or worse. In the immediate aftermath of the Chernobyl Disaster, for example, the Sámi were forced to start pre-Autumn early, slaughtering reindeer before they had a chance to eat too many contaminated lichen, mosses, and mushrooms. Artificial borders, which limit the movement of reindeer and their herders, can derail the calendar too, as does, of course, climate change. In the Sámi calendar, time relies on the landscape and its inhabitants for meaning. Maybe that’s a useful thought for heading into Ođđajagemánnu, New-Year Month: to know what time it is, you have to know what’s happening around you.

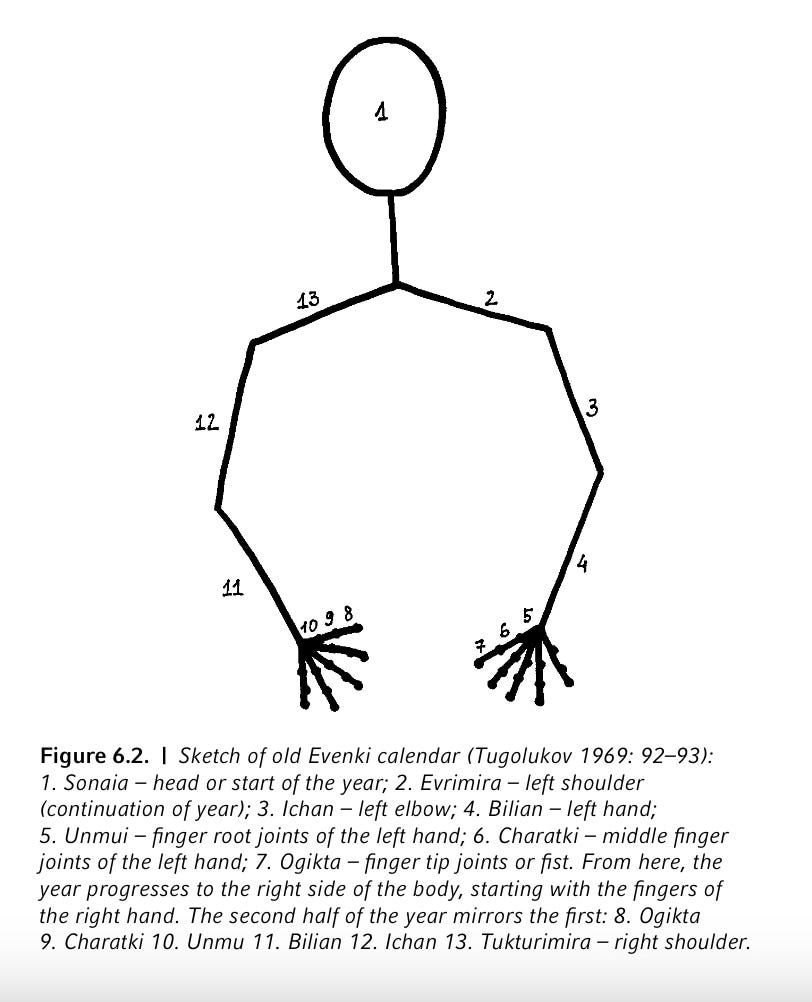

Below is another interesting indigenous Arctic calendar, courtesy of the Evenki people of Northern Russia, China, and Mongolia: starting from the head, the first month begins after the spring equinox, putting Western New Year somewhere around the right wrist. For the Oroquen people of China and Inner Mongolia, the period around New Year’s is known as the “the time of big walking,” because the heaviest snow hasn’t yet fallen and it’s still possible to track nearly thirty kilometers a day hunting wild sable (this is followed, of course, by the time of little walking).

Defining a year solely in terms of a fixed calendar is a kind of luxury: a marker of the fact that some people don’t need to observe unfolding changes in the landscape to know when to hunt, when to leave the mountains, when to return. But it is also an impoverishment, removing the richness of the living world from everyday view. A year is 365 calendar days, but for the Sámi, Evenki, Oroquen and other Arctic peoples, it’s also a flow of crows, swans, blossoms, and lichen, a crust of ice on the snow, birch leaves yellowing on the trees, reindeer grown fat on mushrooms and berries, lakes slowly hardening with ice, each moment blooming, thawing, freezing into the next, from head to shoulder to wrists and back again. Of course, these observations have historically been a matter of subsistence, but what is a calendar, if not a record of the days we’ve survived, or hope to? In any case, I’d like to see—and feel—the world around me so closely in the year to come.

As for the year behind us: I spent 2023 on a project completely outside the purview of this newsletter. I can’t share anything yet, but it has involved building a new world with my best friends. In my own writing, I went long on scale, two ways, for Grow Magazine: making a case against scalability and exploring the history and philosophy of microscopy. For the MIT Technology Review, I did a little biotech reporting and indulged my passion for media archaeology by traveling through the colorful history of the corporate presentation. I published long conversations about intelligence (artificial and otherwise) with writers James Bridle, Sheila Heti, and Joanne McNeil.

I was nominated for (and lost) a National Magazine Award, gave an old favorite the Pop-Up Magazine treatment, moderated a panel on AI and protein-folding, and premiered a visual presentation about the new frontiers of biocomputing at Sónar Festival. Broad Band was translated into German and improbably named one of the “best tech books of all time” by The Verge. A short story I wrote about a future museum of symbiosis was turned into a physical installation (out of mycelium, no less) for the Venice Biennale. My band also released four singles and a video.

I loved the Italian nanotechnologist Laura Tripaldi’s trippy and audacious “technomaterial bestiary” Parallel Minds, about the intelligence of materials. I loved Renata Adler’s elliptical 1977 novel Speedboat, which Meghan O’Rourke described reading as “like being in a snowstorm” (and which I read here in Finland, as snow indeed fell outside the window). I loved The Diving Pool, a collection of three spare and unsettling horror stories by Yoko Ogawa. I loved Stanislaw Lem’s Memoirs Found in a Bathtub, and this album by the Tuareg family band Etran de l’Aïr. I loved walking around my neighborhood every morning listening to audiobooks on Libby. The video game IMMORTALITY blew my mind (more about that soon). Here is a playlist of songs I put on every time I potter around in the garden.

Have a wonderful New Year, however you define it.

xo

Claire