I write this as Southern California experiences its eleventh atmospheric river of the year. The storm drains are overflowing but my backyard—planted with natives and furrowed with water-filtering swales—seems to be handling it well.

It was this time last year, more or less, that I sat down to chat with one of my favorite writers and thinkers, James Bridle, over Zoom. At the time, I remember, the air was warm, the birds were nesting, and some of my early wildflowers had already gone to seed. There are many kinds of gardens, and many kinds of gardeners, but at best I am a grateful visitor in my own. I don’t control what happens there; I’m only a witness.

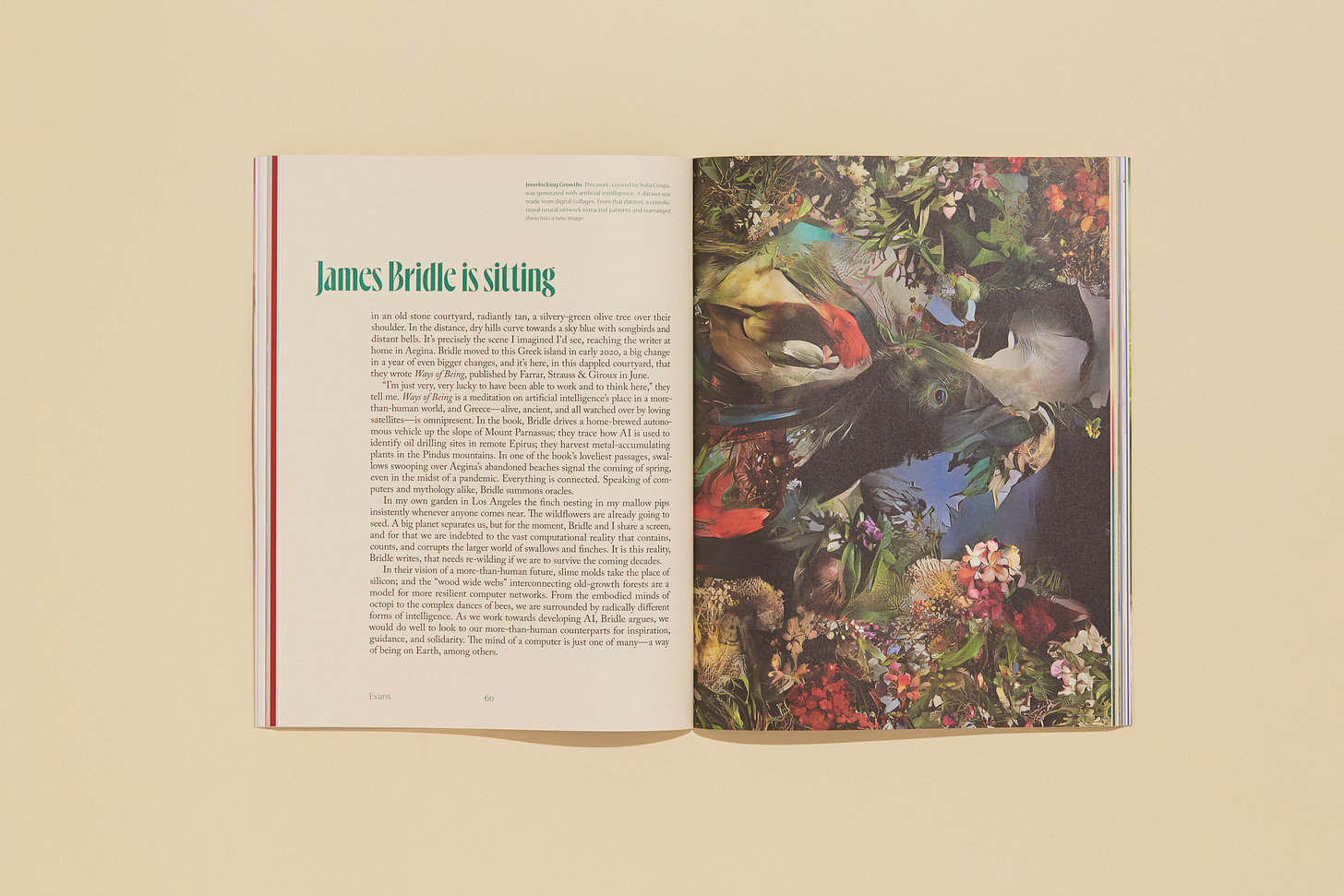

James, too, is a gardener, and the best kind of witness. We spoke just before the publication of Ways of Being, their second book, an ambitious and imaginative call to see the world anew. It is, ostensibly, a book about Artificial Intelligence, but James situates machine minds in the context of a complex living world populated by equally valid forms of intelligence: searching seedlings, clever cephalopods, problem-solving slime molds, computational crabs, networked thickets of trees and fungi.

“Perhaps the advent of intelligent technologies will allow us to perceive the rest of the thinking, acting and being world in ways that are more interesting, more just and more broadly mutually beneficial,” they write. Our conversation last spring, which touched on birdwatching, AI glitches, gardening, the preservation of knowledge and the internet of animals, among other things, was published in Grow magazine’s print Futures Issue—and now it’s finally online. Read it here in full!

As a newsletter exclusive, I thought I’d share a fragment of our conversation that ended up on the cutting room floor—a small digression about science fiction that might double as a fun reading list for plant nerds. James is also a contributor to Terraform, the science fiction anthology I co-edited with Brian Merchant; their short story, originally published online here, is about the global erasure of all personal data.

I love the chapter in your book about plant intelligence, because it reminds me of Gothic horror stories—tales of vegetal horror written as exotic plants were being absorbed into Western taxonomy through the violent expansions of colonialism. For the Victorian plant collectors who crossed the world to steal rare orchids and do oppression, maybe the “nutation” of tropical vines sparked a certain guilty dread. Your book linked that to Darwin for me—it made me understand that the emphasis on the evolutionary importance of dominance and competition served to justify those same behaviors in people. Which makes those Victorian horror stories even scarier. That’s not really a question. Here’s one: what role does fiction play in your thinking?

I read loads of fiction. I just finished John Wyndham's The Trouble With Lichen. I'm a real fan of that particular era—of the 1940s, 1950s, and 60s—but not the rocket ship stuff. More like Ballard, Wyndham.

The Triffids.

Yeah, terrific oddball stuff. The thing that I've been fascinated by is, in recent years, is that a lot of the writers that I like—people like William Gibson and Kim Stanley Robinson—the way in which their fiction has got closer and closer to the present. It seems very significant to me. It's not that the horizon of science fiction has reduced, but more that the opportunities for imagining multiple different futures right from the present have increased in really interesting ways.

I'm also traumatized, a little, by the last 10 years of science fiction as it's permeated culture, particularly in things like speculative design, which have depoliticized those futures to some extent, but also normalized an imaginary that doesn't go anywhere, or take us anywhere. It doesn't actually perform the world-building roles that it claims. I think there's a really extraordinary role right now for fiction to do pedagogic things—just to put the word out about things that people don't know are possible. So much of this book was just reading scientific papers. Because the public understanding of science in the present is decades behind scientific reality across the field. In my book I focus on intelligence, animal behavior, and plants, but it's true for everything, and it's particularly true in physics. We haven't caught up with Einstein yet, let alone everything that's been done since then. Weaving some of those things into stories that are comprehensible to people is amazing work. I'm also super-obsessed with solarpunk as a genuine effort to redirect a future imaginary. I don't think it's doing it very widely at the moment, but really this insistence on really quite radical other futures is so important in the present. Kim Stanley Robinson's recent essay against dystopias, his framing of this work as being anti-dystopian really, really struck a chord.

I feel like it's become more and more difficult to imagine the future because everything's collapsing to a point of inevitability, which makes the past a lot more interesting. And I think that's part of why AI has so entranced the public imagination, because it relies on the past. Training data draws so much from history. We run the past through this randomness machine, and when something comes out the other end, we imagine that’s the future.

It's just like a massive Instagram filter.

Unfortunately. And no one's actually twiddling the knobs quite hard enough in the middle to make something new come out the other end. It's just projecting the same stuff from before into the future. You've written about this.

But that's really nice to think about. I'm more than aware of my hatred of everything retro, but I hadn't understood AI as a completely retro device in that way.

It could be a good thing or a bad thing. It could be a tool for helping us to understand how we got to where we are, but it's not necessarily used in that way. Because maybe we lack the self-reflection necessary to make change.

In other news:

🌱 My piece about the great lost hacker Susy Thunder, for the Verge, was nominated for an ASME Award in the profile-writing category. The ceremony is at the end of the month; wish me luck!

🌱I’ll be in Boston next month for Ferment, the synthetic biology conference, moderating a panel about using AI to design enzymes and giving a special presentation of my piece on molecular ethics, “A Feeling For the Organism.”

Hope you’re reading Becky Chambers! The only fiction writer I know creating worlds I actually want to live in.

Is the talk you're giving at Ferment going to be recorded by anyone? I tried to get tickets but I didn't get an email response and the code for the eventbright page didn't work :(