Note: the following essay about the late artist Robert Irwin and Star Trek production design was originally published in the Art Los Angeles Reader in 2018. I’m sharing it here to commemorate Irwin’s passing this week, and for posterity, since it’s never been published online. After this, we’ll return to a slower email pace.

A corridor is not so much a feature of architecture as it is a consequence of it. Corridors are what’s left over after all the other rooms have been built. They’re most present in structures with many rooms: hospitals, schools, prisons.

Airports, having no rooms, are only corridors.

The American artist Robert Irwin, contemplating a project to redesign the Miami Airport in the mid 1980s, argued that unlike train stations, which showcase the drama of departure, the architecture of airports is “keyed to downplaying and disguising, and even masking, the essential nature of the experience.” Passengers travel along corridors with the assistance of moving walkways; even boarding, they're sheathed in a special-use corridor leading directly to the door.

If popular science fiction is to be believed, corridors will persist as a key feature of travel, even in the far reaches of space. They may harbor horrors, as in the Alien ship Nostromo, or they may double back on themselves in loops, as in the centrifugal corridors of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s centrifugal halls. But they will remain.

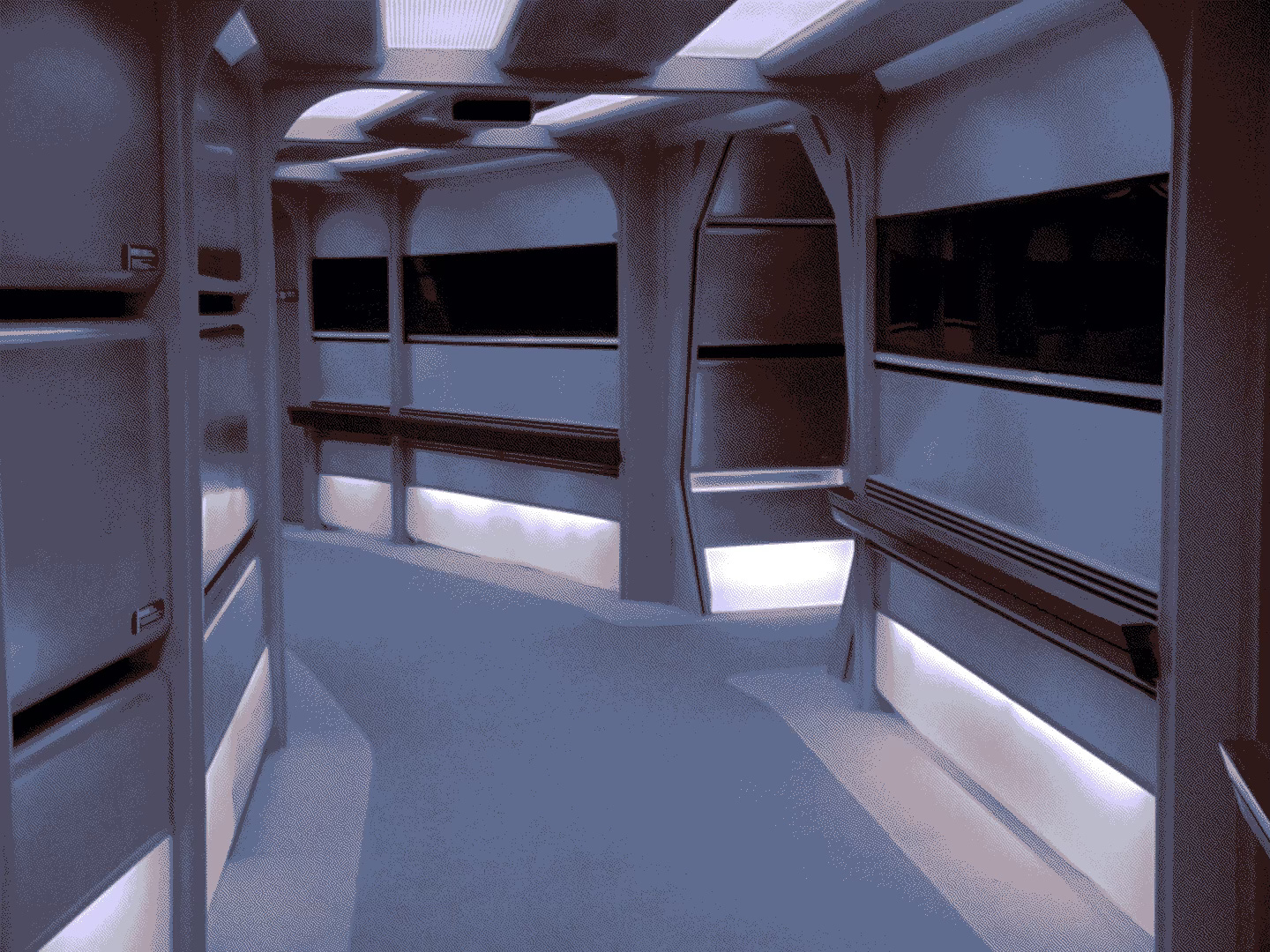

Nowhere in the science fiction canon does the corridor live more vividly than in Star Trek. If a crew member of the USS Enterprise is not on the main bridge, the holodeck, sick bay—or anywhere else on the Paramount lot—she is pacing its corridors, where “com panels” allow ship-wide messaging and wayfinding screens of orange and purple light are conspicuously free of thumbprints.

It’s in these corridors that Star Trek’s central illusion is conveyed: that the ship is a galaxy-class cruiser bearing some thousand souls seeking “new life and new civilizations” in uncharted space. Nowhere else aboard Enterprise are we given a clearer indication that lives and stories unfold beyond those in narrative frame. Young ensigns dart, tricorders in hand. Couples wander, off-duty. An alien priest in ceremonial garb strolls under escort.

In reality of its production, the longest possible walk along a Star Trek set corridor was five minutes at a slow pace. In the show, crewmembers could amble for hours. That’s good old practical TV magic: watch closely and you’ll see actors passing the same turbolift doors again and again. Through repetition, endless promenades unspool from within the prohibitively tiny frame of standard-definition television.

In the late 1960s, as Star Trek: The Original Series was airing on American television, Robert Irwin was also thinking about evoking vastness from within the equally prohibitive frame of a painting. He succeeded, after much experimentation, with his “dot paintings.” On these white canvases, small red and green dots—not dissimilar, on close inspection, to the red and green pixels of a TV screen—created a visual bloom, a “blush,” as one critic wrote, awakening the eyes to the act of perception itself.

To “render the edge as mute as possible,” Irwin painted on canvases stretched over slightly convex frames, so that their edges seemed to “fall away” and the “sense of the central dot hive became further energized.” This is a bending of space-time, an opening in the continuum on par with a Warp Speed blink into a dot-field of stars, or the corporeal dematerialization of a transporter beam.

Like Trek's generations of set-builders, Irwin was maniacal about craft: testing shades of white, red, and blue paint, forming and finishing his canvases. And, like Irwin, those set-builders, painting, lighting and compositing new worlds, made it possible for audiences to see the unseeable (and, to quote Douglas Adams, eff the ineffable).

The dot canvases were Irwin’s last paintings, before he reimagined himself as an installation artist and then a producer of frequently unrealized “site-conditioned” works at romantic landscape sites across the world. After the dots, he began producing polished aluminum discs, which he lit sideways with complicated custom rigs until they seemed to disappear into their own shadows. Irwin’s fixation with lighting, and eventually light itself, could only have emerged in Los Angeles: a city whose core industry was built on the quality of its light, and whose flat sun would give Irwin’s early installations in his Venice studio their characteristically ambiguous haze.

Irwin famously loved to drive, and in the late ‘60s he made long car trips through Los Angeles' industrial parks, from one fabrication site to another, searching for the right hand to hammer out his discs, until he found “a beautiful guy” at a metal-shaping shop in Downtown LA that specialized in custom pieces for aerospace and automotive applications. Irwin always approached fabricators as a “store-window decorator,” believing his fastidious requests would be more palatable if they were understood as commercial specifications. Perhaps, as he toured LA’s factories and workshops, he crossed paths with Star Trek’s own set decorators, who, like him, were boldly seeking the right material finish to represent five inches of infinity.

And infinity, in Star Trek, has always been material. Before CGI, its illusions were built by hand by seasoned craftspeople earning union wages: set-builders, model-makers, and matte painters, that hidden class of artists specializing in landscapes diffusely painted on glass and overlaid, as composites, onto finished shots. Star Trek has historically relied on mattes: the series’ largest corridor complex, created for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, was a short set bookended by trompe-l'oeil paintings. This was the inverse of an Irwin gesture: in such frames, the painting begins at the edges.

Deep Space Nine, incidentally, is all corridor: the station, hanging at the mouth of a wormhole, has at its center the Promenade, a radial corridor ringed by shops and temples. Much of it is lit from overhead, in grids of spot lights, creating an Irwinlike diffusion of illuminated dots. Irwin might have appreciated this, if he’d had the bandwidth for television; he understood the corridor’s seemingly contradictory proposition of propulsion and limbo, its role as a perceptual shaft, concealing and focusing attention towards the passages ahead.

Rooms, with their proscribed uses—kitchen, quarters, living room, holodeck— assimilate us into domestic roles, but corridors, unspecified, return us to our bodies. Moving through them, we are alone with ourselves. We are undefined. We are aliens.

Robert Irwin’s largest site-conditioned work, commissioned by the Chinati Foundation in 2016, sits on the site of an abandoned army hospital. “The only permanent, freestanding structure conceived and designed by Irwin as a total work of art,” untitled (dawn to dusk) is a right-angled horseshoe, essentially a single concrete corridor split lengthwise on the inside by one of Irwin’s signature effects: taut, sheer scrims. The light in untitled (dawn to dusk) comes only from tall, evenly spaced windows giving out onto the searing, heartbreaking blue of the West Texas sky. “The clouds are right on top of your head,” Irwin has said of the landscape.

Beyond that, the stars.

RIP Robert Irwin, 1928-2023.

Further reading:

No mention of Irwin’s work is complete without a shoutout to Lawrence Weschler’s incredible study of Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, to which I owe this essay’s airport anecdote and several other details.

Just a weird concordance I might as well mention here: the most exacting renderings of the USS Enterprise’s network of corridors were created by the technical illustrator David Kimble, famous for his stunning airbrushed cutaways of sports cars, airplanes, and electronics. The son of an aerospace engineer, Kimble was hired in 1974 to create the “official” blueprints for the Enterprise, used in the construction of models and sets for Star Trek: The Motion Picture. For decades, he has lived and worked out of a converted movie theater in Marfa, a few miles from Irwin’s ultimate work.