We all have one: three pounds of winkled grey-pink peering out at the world from behind castle walls of bone. It’s the seat of consciousness and dreams. It holds memories, harbors love, shocks with fear, awe, and pain; it works over the raw input of the senses, smoothing the chemical signals, wavelengths of light, vibrations and electrical messages it receives into a cogent picture of its realm.

Yep, that’s a brain—mine and yours, the same brain that brought us language and agriculture, that threw the first spear. The same an unnamed scribe first etched into papyrus some 3,500 years ago (searching for the right hieroglyph, he chose “skull-marrow,” something to scoop out when the time comes for mummification, favoring that glorified muscle, the heart, for transport into the realms of the Dead).

It’s the same brain Aristotle had, and used, in his wisdom, to ponder its purpose: certainly nothing important, perhaps a cooling system? The same the 20th century neurologist Sir Charles Scott Herrington called “an enchanted loom.” Bless them all, it’s the only brain they had, but it’s far from the only brain there is.

Cognitive science has long taken the existence of a nervous system as a prerequisite for intelligence. But neurons aren’t magic or unique—they only perfected what simpler cells had already been doing for millennia, and continue to do everywhere on Earth. Bacteria make collective decisions using chemical signals similar to those found in cortical brain activity. Cells come together to form complex structures. Slime molds make decisions, sometimes even irrational ones. And if memory is the capacity to modify behavior based on past experiences, then sperm, amoeba, yeast, slime molds, plant cells, and single-celled organisms all have memory.

Cognition isn’t reserved only to vertebrates with language, reason, or self-awareness. There are more primitive cognitive subsystems within us, around us, and all along the ladder of evolutionary time. Studying them is the purview of an emerging interdisciplinary field in biology: “minimal cognition” or “basal cognition.”

The philosopher of science Pamela Lyon writes that “taking seriously modern evolutionary and cell biology arguably now requires recognition that the information-processing dynamics of ‘simpler’ forms of life are part of a continuum with human cognition.” Not to be outdone, biologists František Baluška and Michael Levin have suggested that cognition is a fractal, spanning nested levels of biological organization. “Whether each successive level of organization is in some sense smarter than the ones below it, or whether structures derive their cognitive powers from those of lower levels, remains to be discovered,” Levin and Baluška write. They don’t concern themselves with big-C consciousness, the so-called “hard problem” of cognitive science. Instead, by learning how these more minimally cognitive agents function, they propose that we might someday be able to tackle the hard problem from the (squishy) bottom up. I think that’s exciting; it makes the whole world a brain.

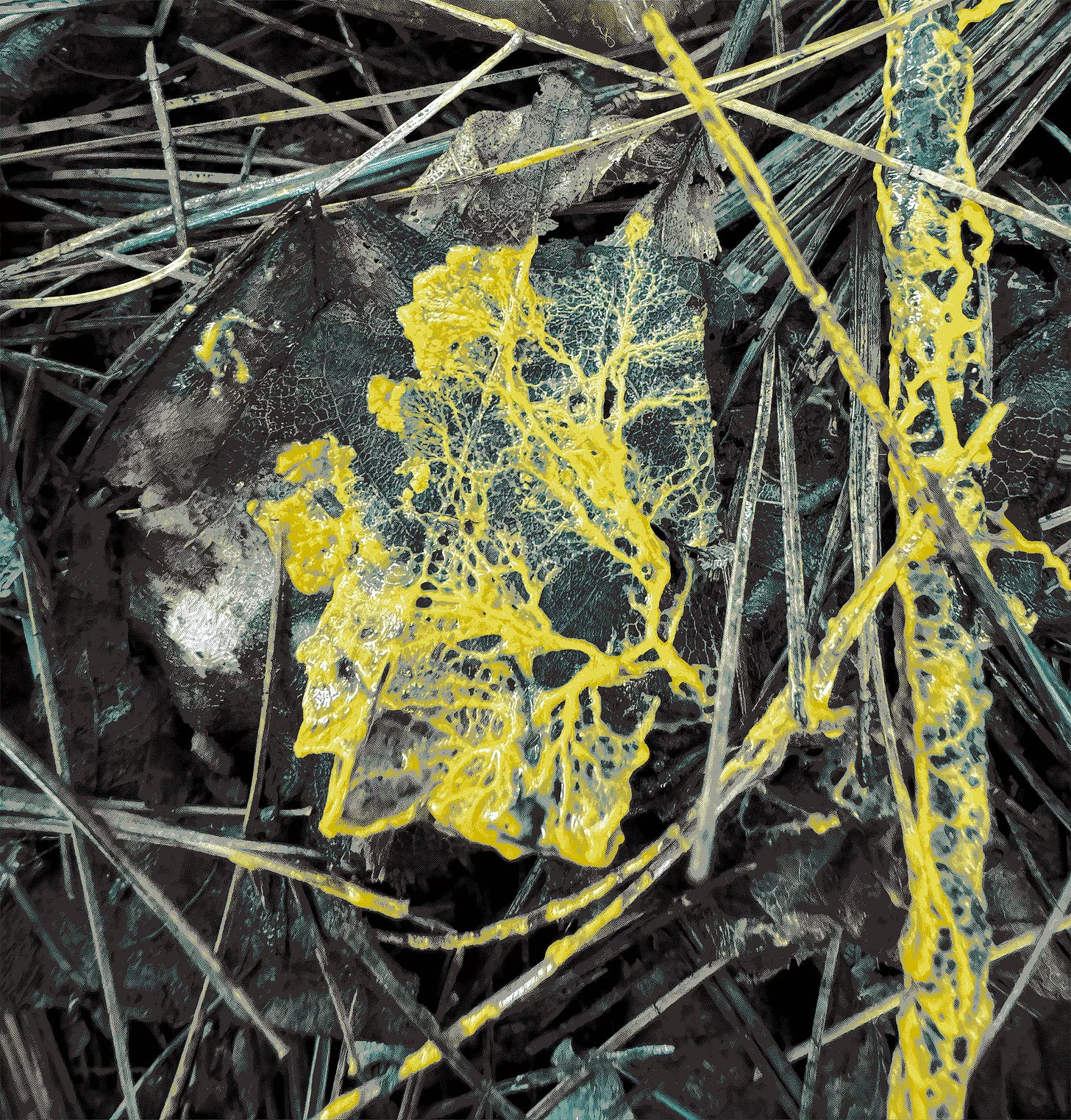

I came to minimal cognition in the course of my ongoing research (read: obsession) with slime molds, which, in certain contexts, display computational capacities to rival our fastest computers. Physarum polycephalum can solve combinatorial mathematics problems and model resilient networks so effectively that there’s been quite a bit of wet lab-tinkering to bend them into primitive bio-computers. One study in 2016 even injected conductive nanoparticles into the slime molds’ plasmodial tubes to see if they could be made conductive, suggesting future Physarum chips. Initially I thought this was the most interesting thing about slime molds: that they do computer stuff.

Now I’m torn. Are slime molds a new computational substrate, or do we just use computers as measuring sticks, a way of imposing value on the living world? If an organism is “like a computer” doesn’t that make it an object, something that can be instrumentalized towards a purpose—that is to say, ours? As any researcher who works with them will tell you, slime molds aren’t objects. They’re subjects, and quite willful ones. When I spoke to the Australian systems biologist Chris Reid, who has done extensive work with Physarum, he told me that his specimens are always escaping the lab. “Sometimes the best slime mold to use for your experiment is the one that's just crawled out of the bin,” he said. “They have a real zest for life.”

When the popular press covers slime molds, they tend to emphasize how remarkable these brainless organisms are at seemingly human tasks—like, famously, recreating Tokyo’s regional commuter rail network. But that’s backwards. Networks are a fact of nature, and slime molds are much better than us at creating networks that are both minimal and robust, balancing efficiency with redundancy. “That's where it makes real sense to give the problem to the slime mold, see how it solves it, and try to extract principles that we can use to make our systems better,” Reid explained.

That is to say, in order to get useful answers, it helps to meet the slime mold where it’s at. Other organisms may help us to answer different questions. And if we align our questions with the inherent capabilities of the organisms we employ in our computational experiments, we can yoke together our interests, too. Maybe that’s why I’m so interested in minimal cognition. Not only because it opens up the definition of what a brain can be, but because it binds us to the world, drawing our brains into a broader phenomenon that touches life at every level. We’re nothing special. As Reid said to me, laughing, “in some ways, it's information processing all the way down.”

The terms “information processing” and “computation” show up all over the minimal cognition literature, and in biology more generally. This threw me, initially. But it doesn’t mean that slime molds, cells, or bacteria are like computers. It just means that the underlying principles of computation transcend their medium. Living systems store information in order to make better decisions in the future—those who remember danger avoid it later. We humans simply use computers to outsource that remembering and tailor its scope. If you’ve read James Bridle’s essential Ways of Being, you may recognize in this idea that book’s persistent mantra that the world is not like a computer, but a computer is like the world.

Anyway, this is mostly what I thought about during my precious month at MacDowell, where I worked on two books, slept with the windows open during the summer storms, spotted meteors, newts, and mushrooms, and learned to feel safe in the dark.

In other news:

New Release, the new album from my band YACHT, is out now on all platforms! Listen on Spotify or Apple Music; pick up the LP on Metalabel or Bandcamp.

The nice people of Longreads included my piece for Noema Magazine on lucid dreaming in their weekly Top 5, calling it “brain-bending in more ways than one.”

On October 12th, I’ll be in conversation with Jonathan Lethem at Hauser & Wirth’s bookshop, ARTBOOK, here in Los Angeles. We’ll be talking about his new book, Cellophane Bricks, a “stealth memoir of his parallel life in visual culture.”

xo

Claire

i saw “Ways of Being” in a bookstore last year and it piqued my interest. Its been sitting in my queue ever since. All the more reason to read it now!

Food for thought as always Claire, thank you..... a colleague Neill Friedman at Northampton Uni is entirely immersed in his research on mitochondria at present and their role as energy factories in our cells......a fascinating link to our primeval origins.