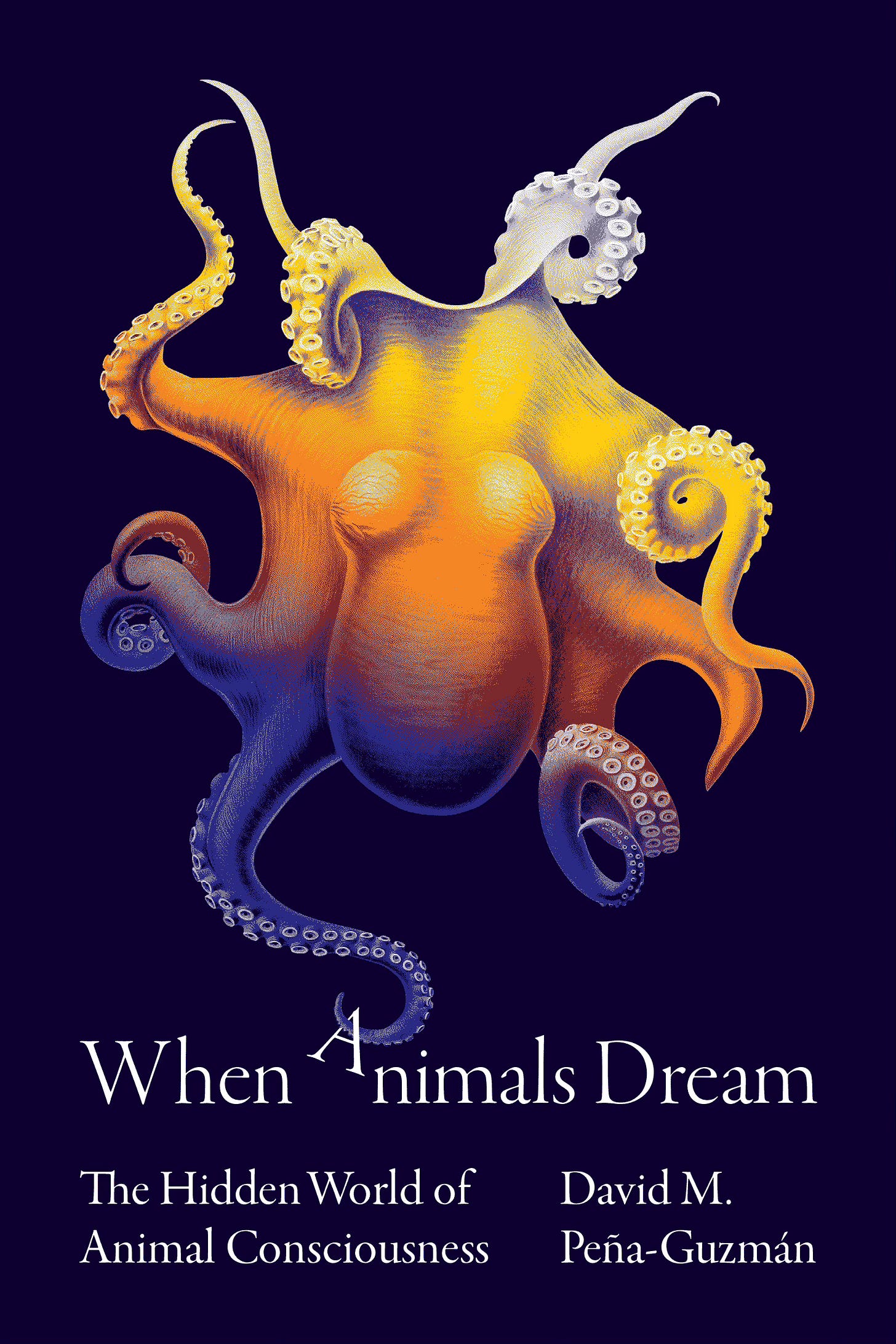

When Animals Dream

A conversation about animal dreaming with philosopher David M. Peña-Guzmán.

Anyone with a pet knows, intuitively, what many biologists still hesitate to admit: that animals are dreaming beings. “Like us,” writes the philosopher David M. Peña-Guzmán, “they are builders of worlds, even after the Stygian currents of sleep have pulled them under and sent them flying through the looking glass.”

Peña-Guzmán is of a school of contemporary philosophers who work closely with scientific material, unpacking the implications of laboratory research on our understanding of consciousness. In his 2022 book When Animals Dream, he draws from behavioral and neuroscientific research on animal sleep to make the case that not only do many animals dream, but their dreaming is evidence of phenomenological consciousness: the capacity to sense, feel, and experience the world. As such, he argues, dreaming, rather than forming language, suffering, or making rational judgments, is what confers moral status on animals. Because they dream, animals are conscious beings “who matter, and for whom things matter.”

It’s a fascinating book—packed with daydreaming rats, hallucinating monkeys, and the silent songs of sleeping finches—and Peña-Guzmán’s argument is lucid and deeply felt. We spoke over Zoom this week; I’m giving you some highlights below.

Let's start with something a bit personal. I wonder if spending years thinking about the dreaming lives of animals has had an effect on your dream life.

I had a dream that really marked me once, in which I was wearing a white lab coat, and I was with a group of other scientists hovering over a sleeping rat in a laboratory setting. I think this was, partly, an anxiety dream—about my own anxiety about using scientific research to make an argument about animal minds and animal ethics, knowing full well that a lot of the research that I use doesn't meet my own standards of ethics. This is something that I have been struggling with in my work: what it means to work in close proximity to scientific protocols that often kill animals.

It's clear from your work that you're profoundly attuned to animals, and you care deeply about the ethical and moral responsibilities we have to them. But yeah, your book does include a number of quite brutal laboratory experiments as evidence.

I'll be very honest: I had a lot of anxiety about this. I had to do some soul-searching about what exactly my goals are, and what it means to pursue them. I'm not sure that I'm satisfied with my own answer to this issue. I still sit uncomfortably with it. The way in which I've thought about it, up until now, is that perhaps we can use some of this research that's been produced by scientists to launch an internal critique. To show: look, based on these experiments that you've already done, the image of animals that you have, and that you use to justify your experiments, is overturned. Because the image that emerges of animals from this research is of sentient, complex, sensible creatures that therefore trigger moral considerations. One thing I will not do is call for more of these experiments. That is inconceivable. I'm not going to call for more experiments proving that animals feel pain. The evidence has been there for a very long time.

Your argument for animal dreaming draws analogies between the neuroanatomy, electrophysiology, and the behavior of animals during sleep and our own. But you also write that "other than anthropocentric conceit, we have no reason to expect that other animals dream in the same way that we do." How is our dreaming similar, and how is it different?

What I have in mind here is a distinction between, let's say, structural and functional similarities. I'm giving all these reasons to believe that other animals can dream. But how they dream—that's not something that I touch upon, except in a few cases where the science does give us insight into some elements of the content of their dreams. You can think about it as a form versus content distinction. I think animals have the form of dreaming, the capacity, but then they fill it in the same way they fill the world of waking experience, which is to say with their own sensory capacities, with their own bodily limits, and capabilities, and so on. There might be other animals that have the same sensory modalities that we do, but that don't give them the same weight.

For example, humans are highly visual creatures. A third of the cortex is dedicated to visual processing, and so even from an anatomical perspective, vision takes up a lot of real estate in the brain. Most of our dreams tend to be visual. But there are animals that see, but that don't see well, and for whom seeing is pretty much a backup sensory modality. In that case, I think it's fair to suspect that they will have dreams where there is not a lot of visual content. Think about an electric eel that senses and produces electricity. That's a sensory modality for that creature. It's conceivable that an eel will have electric dreams, and there’s no way for us to even imagine what that is, because we don't know what it means to experience electricity as meaningful. But they do. That's the sort of thing I mean: that they will dream, but not like us.

“An eel will have electric dreams, and there’s no way for us to even imagine what that is, because we don't know what it means to experience electricity as meaningful.”

This reminds me of the concept of the umwelt, the perceptual sphere of an animal. Could you say that an animal's dream is its imaginative umwelt?

I think that's exactly what a dream is. I think a dream is an imagined umwelt. When people talk about the umwelt, they talk about it like it's a bubble that engulfs the animal in which it is immersed. In this case, it's imagined in a much more radical sense than our waking umwelt, but both of them are imagined. It's just that you see the construction much more clearly, in the case of the dream.

Animal dreams, like their perception, will always be unavailable to us. My cat will never be able to describe her dreams to me, but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t dream.

Often the barrier that those of us who work in this field have to jump over is the issue of language. How do you know [animals dream] when animals can't talk about it? Often we navigate that by saying, well, you can have the experience without having language, because although language might add something to the experience, it doesn't constitute the experience. An example of this is the idea of thought itself. For a long time, thought has been described as having a linguistic form: to think is literally to think in a sentence. But you can think visually, and a picture is not a sentence. It doesn't have a linguistic structure. There are no verbs, there are no subjects and nouns. Philosophers are really invested in making things linguistic and I just believe that's a mistake. And it's been a mistake for a very long time.

An anecdote that blew my mind in your book is that while there's evidence of dreaming in mammals, lizards, birds, and even fish, the jury is still out on cetaceans. Of all the animals that I feel certain must dream, dolphins are at the top of my list.

It's not that there isn't evidence of dreaming in cetaceans, it's that cetaceans are the most contested case. And that has to do with the style of their sleep cycle. Dolphins have hemispherical sleep: they fall asleep with only half of their brain, while the other half is awake and alert and interacting with the world. They keep half of their brain awake, because they have to go up to breathe, otherwise they would drown, and because they have to follow the pod that's constantly moving. And so some people have said, logically, that they wouldn't be able to dream, because a dream is something that you get immersed in, and a dolphin can't get immersed in a dream and still be actively interacting with the world in a coherent way. But the fact that it's inconceivable to us doesn't mean that it's not materially possible for them. Who knows? It could be that they have a split-screen vision, where half is dream, half is reality. Maybe it's a combination of the two. Maybe they switch back and forth, changing channels between reality, dream, reality, dream. We don't know whether or not they dream. Some people have noticed indicators of REM in whales and dolphins, others have looked and have not found them. My position on this is that I just don't want to close the door too soon merely because we can't comprehend it.

When Animals Dream opens with an anecdote about Heidi, a female day octopus caught sleeping in a 2019 PBS Nature special. As she sleeps, Heidi’s dreams appear to play across her skin in a stunning chromatic display; she flicks from white, to orange, to wine-dark purple and finally light gray and yellow, in a sequence, Guzman suggests, that’s almost narrative in quality. If you’ve never seen the video, it’s really remarkable:

When Animals Dream is available here. David M. Peña-Guzmán is also the co-host, with Ellie Anderson, of Overthink, an excellent and very approachable philosophy podcast that tackles a wide range of subjects ranging from animal justice and standpoint epistemology to psychedelics, orgasms, and AI.

In personal news: a few weeks ago I joined the designer Mindy Seu and Yasaman Sheri, principal investigator of the Synthetic Ecologies Lab at the Serpentine Gallery, for an online seminar hosted by the School of Visual Arts. We talked slime mold, ferments, networks, and interspecies collaboration, among other things. The video for that session, The Algorithmic State: Wetware, Fermented Code and Artistic Inquiry, is now on YouTube if you’d like to watch.

xo

Claire

If you wanted to dive into neuroscience research on emotions, this book was pretty thorough and starts off with a whole thing about the trade offs of animal research (link to my review) https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/170777320