In 1971, the astronaut Stuart Roosa, a former U.S. Forest Service ranger who’d logged his first flight miles smoke-jumping wildfires in Oregon, brought a forest into space.

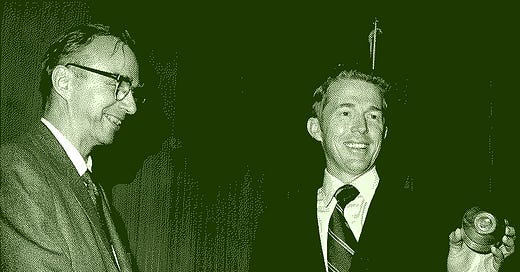

Tucked into Roosa’s personal kit, hundreds of pine, sycamore, sweetgum, redwood, and Douglas fir seeds made a historic 34 laps around the moon. When Apollo 14’s crew returned to Earth, they spent two weeks in an isolation chamber, and the forest underwent decontamination, too. Under pressure, the seed canisters burst, scattering the seeds and exposing them to a vacuum. NASA would have left them for dead, but Stan Krugman, the geneticist in charge of the project, intervened to salvage and sort them.

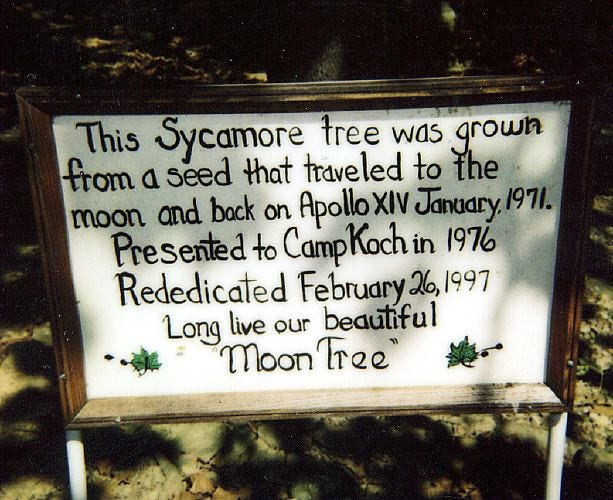

From these, some 450 “moon trees” germinated, and by 1975, the seedlings were hardy enough to plant out. The US Forest Service put out a call to state foresters, offering the trees on a first-come, first-serve basis. “It was part science, part public relations,” Krugman joked at the time.

The timing was perfect. The 1976 bicentennial was just around the corner, and moon tree planting ceremonies seemed like an appropriately solemn way to celebrate America’s sprint from revolution to the stars. The trees were planted at state capitols, museums, schools, and courthouses in 40 states. Then-President Gerald Ford sent out a telegram to be read at all the tree-planting ceremonies, praising the moon trees as “living symbols of our spectacular human and scientific achievements.” He had a moon pine planted at the White House. Everybody drank Tang afterwards.

Today, the White House moon tree is dead. As are all seven moon trees planted at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, and the moon sycamore at Cape Canaveral. In fact, less than 100 of the moon trees remain, although that number is approximate: having passed stewardship of the trees onto the states, neither NASA nor the Forest Service kept any official record of where the moon trees were planted. For decades, as they put down roots, the moon trees were completely forgotten.

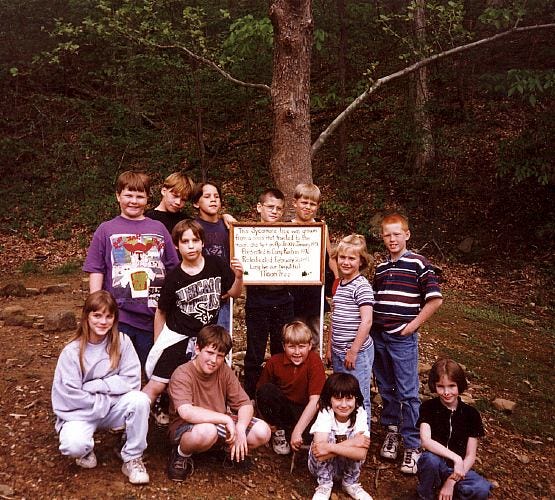

That might have been the end of the story: a forest of moon trees, isolated from one another, exposed to a vacuum of indifference. But in the early 1990s, a third-grade teacher in Cannelton, Indiana learned about a moon Sycamore planted at a nearby Girl Scout camp. Unable to find any information, she sent an inquiry to NASA.

Her email landed in Dave Williams’ inbox. Dave isn’t a historian; he runs the Space Science Data Archive, the NASA department responsible for restoring Apollo-era lunar data. “I was like, ‘I've never heard of this before in my life,’” he told me when I reached him over Zoom. “But I knew a lot of the old-timers at Goddard, so I went around, and I asked them—no one had heard of it, no one knew anything about it.”

He started digging through newspaper archives and posting clips online. It was the early days of the World Wide Web, and information was scarce. But people who came across his site submitted moon tree sightings and bicentennial memories. Bit by bit, his bare-bones, unofficial archive became the only repository of known moon tree locations. Over 30 years, it’s brought him into contact with state foresters, park rangers, archivists, and even the Vatican astronomer. But he never met Stuart Roosa, who died in 1994. “We're losing the astronauts,” he says. “In fact there may come a day when the only the only living things that have ever been to the moon are these trees.”

The moon trees have descendants, second generation “half-moons” grown from the seeds of a mature moon Sycamore at Mississippi State University (you can buy one here, from a Tennessee nursery that also offers a pecan tree from Alex Haley’s childhood home and Helen Keller’s favorite magnolia). Fittingly, Stuart Roosa’s own descendant—his daughter Rosemary—offers half-moon planting ceremonies in memory of her Dad. In 2022, having rediscovered the PR possibilities of the project it had ignored for a half-century, NASA flew a fresh batch of seeds around the Moon on its Artemis I mission. Those will be planted soon; the legacy continues.

Last year, I pitched a version of this story to a magazine, suggesting that I could round out the piece by visiting the moon tree plantings closest to me, along California’s central coast. The editor, very kindly, told me this might be boring for readers. After all, the moon trees are just trees. Their provenance gives them no discernible aura, no exotic mutations. They don’t grow upside-down or sideways. “What’s less space-age than a tree?” says Williams. This is precisely why I like the moon tree story so much.

Trees are wonderfully indifferent to narrative. Every historic tree I’ve ever visited—from the “Major Oak” in Sherwood Forest to the 5,000-year-old ancient Bristlecone pines of Northern California—has been, its own way, utterly normal. Plaques nearby always insist otherwise, of course: this tree has been to space, this tree saw the rise and fall of empires, this tree sheltered Robin Hood. But trees know better than to let our stories dictate the value of their lives. Who the hell is Robin Hood, to an oak?

In the late 1980s, the “space philosopher” Frank White published a famous book called The Overview Effect, which argued that seeing the Earth from space triggers a state of transcendent awe that irrevocably changes astronauts’ perspectives. White’s theory is poetic enough, but in the hands of space industry boosters, it’s given moral weight to the idea that humanity is fated to expand to other worlds. If astronauts return to Earth transformed, then we should all be astronauts, White suggests—in fact, it’s our evolutionary imperative to colonize other worlds. But the original moon trees, unchanged by their journey, are perfectly happy putting their roots down here on Earth. Maybe we should be too.

In other news, The Computer Accent, the feature documentary film about my band YACHT’s early experiments with machine learning and music, is finally available to rent or buy on AppleTV and Prime Video. It was filmed in 2017, and although it’s already become a time-capsule of creative AI during what turned out to be a transformative moment, the central thesis of the film—that music documents experience, and that the role of technology shouldn’t be to make those experiences more efficient, but rather to enliven and complicate them—remains solid.

I did a long interview about the film and my thoughts on AI now with AllMusic, if you’re interested, and the filmmakers have also released an extended cut, in podcast form, of one of the film’s most interesting conversations, with the algorithmic music pioneer Dr. David Cope, who started making generative music systems in the 1980s. Visiting Cope’s office in Santa Cruz is one of my favorite memories of making this film; every inch of the ceiling was covered in wind chimes, and when the window was cracked open, a gentle breeze from the sea made the most lovely music of all.

xo

Claire

We've got a coastal redwood moon tree at the State Capitol you could visit the next time you tour through Sacramento 😉

I had never heard of the moon trees and (sorry unnamed editor) I would happily see and hear more about this.