I’ve only lost my body once.

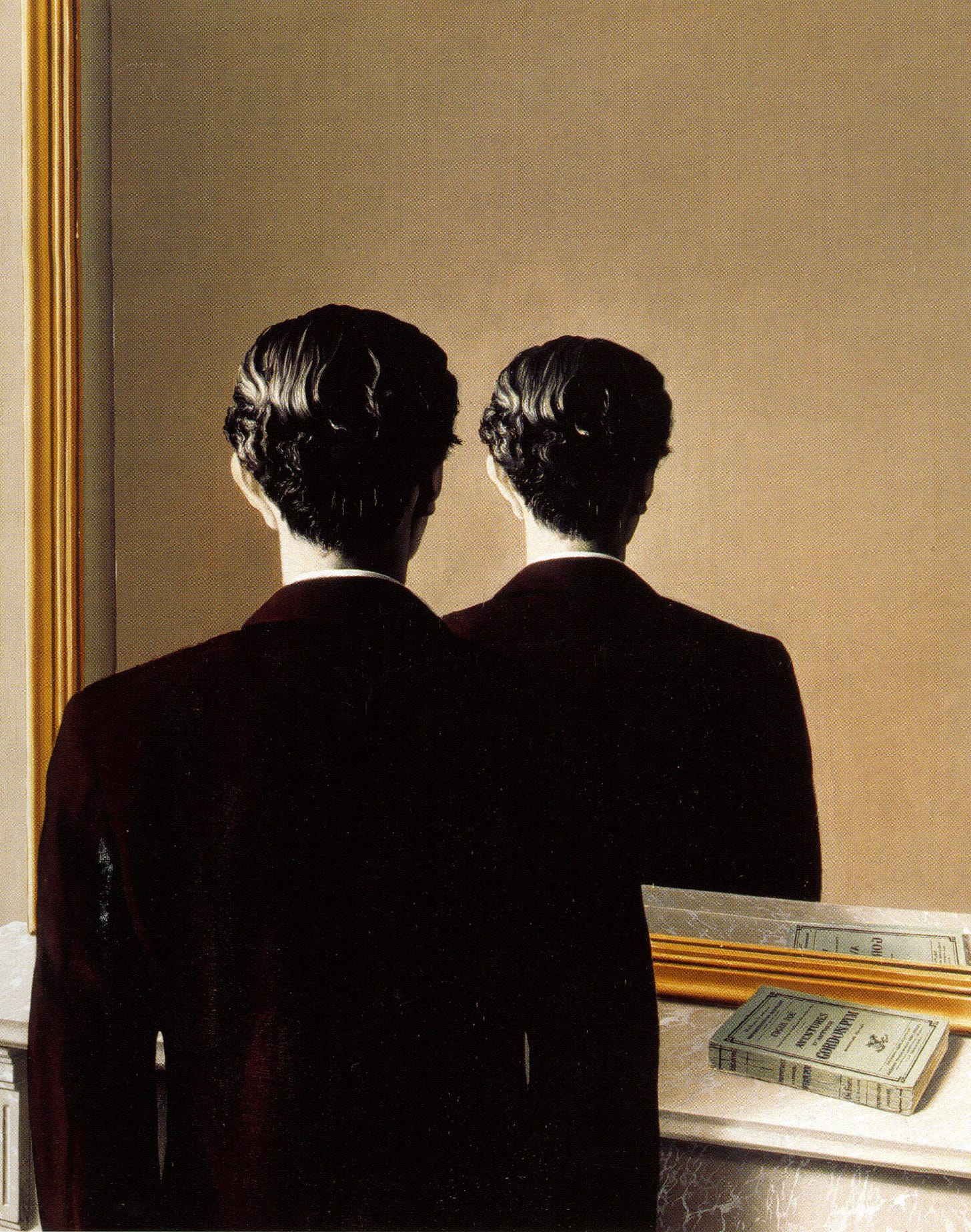

I was thirteen, four days into a weeklong trip to the East Coast with my eighth-grade class. We’d just visited the Liberty Bell, and my friends had already gathered in the back row of the Peter Pan bus that would take us to our next destination. We’d all stayed up late the night before, and I was half-sleepwalking down the aisle. My friend Carly stood with her back to me. That morning, she’d borrowed my shirt. Seeing her from behind, in my clothes, slouching the way all teen girls do, I suddenly felt as though I was standing behind myself. I can’t explain it, but Carly was me. She didn’t look like me; she was me. And I was on the outside, looking in.

My out-of-body experience was brief, but so vivid I had to grasp the back of a pleather bus seat to steady myself. After it passed, I was dizzy with confusion. How could my brain lose the plot in such a spectacular way? Of course, adolescence is a time to experiment with identity, but this went way beyond that, into the realm of bodily ownership—my most elemental, perceptual sense of myself.

This strange moment came back to me recently, as I was researching a piece about the neuroscience of prosthetics. In 1998—the same year Carly stole my body—two Princeton neuroscientists published a paper in Nature documenting a perceptual phenomenon called the “rubber hand illusion.” With a simple experimental setup, they lured healthy participants beyond the boundaries of their own bodies, by tricking them into experiencing a rubber hand as though it were their own. The experiment spawned countless imitations and iterations: supernumerary hands, invisible hands, and virtual-reality illusions of full body transference. In VR, under the right conditions, you can convincingly shake hands with yourself.

Our bodies, it appears, are quite easy to lose. And yet our sense of ourselves as existing within our bodies feels inalienable. It’s deeply engrained, the product of a lifetime spent in our own skins. These perceptual illusions reveal, however, that body ownership is fickle. It’s not absolute and unchanging; it’s something our brains construct for us in real time.

I’m no neuroscientist, but when I read about this, I had to try the rubber hand illusion for myself. My out-of-body experience as a teenager—the ultimate field trip—made me think I might be particularly susceptible to losing myself. I picked up a manicure practice hand from a local beauty supply shop and set up the experiment at home:

The illusion happens immediately. As I watch the brush graze the dummy hand, I can feel the sensation of bristles grazing the inanimate rubber. Intellectually, I know it’s not my hand. I know I bought it, for nine dollars, that afternoon. But that doesn’t matter. The sensation is beyond logic, pinging some slumbering part of my brain: that rubber hand is mine. I feel it.

I had a lot of questions. I tried to answer them with “The Invisible Hand,” my new piece for Pioneer Works. What does it mean to be in a body, to be embodied? Can we change our bodies without changing our minds? I talked to a neuroscientist who works with upper-limb amputees to study how the loss of a limb alters cognition, a congenitally one-handed disability advocate who opts not to use a prosthetic in her daily life, and an industrial designer who has created a robotic “Third Thumb.”

It turns out that although we may be able transfer perception to VR bodies and rubber hands, our cognitive capacity for limbs is finite. Adding an extra thumb to your hand sends your motor cortex for a loop—in fact, it may not be possible to onboard an additional limb without trading off the use of an existing one. This “neural resource allocation problem” may prevent us from ever becoming cyborgs. Research in this domain is active, but young. There’s still so much we don’t understand about the basic experience of being in a body. I keep the rubber hand on my desk now, a gentle reminder that where I end and the rest of the world begins is a matter of perception.

It’s been an experimental year, I guess. I’ve spent it looking for unexpected stories to tell at the intersection of computation and biology. I think what I’ve really been searching is something to make technology feel meaningful to me again—to make it feel, for lack of a better word, alive. And indeed life is the thing that ties this year’s experiments together. Working on stories about early Artificial Life research and biological robotics, I chased traces of life in the machine itself. Writing about prosthetics, I looked at how life interfaces with technology. Writing about decentralized forest networks, I drew metaphors from the living world that might help us build a more humane internet. And writing about cultivating empathy for bacteria, I chose to honor that living world, no matter how small.

I’m very grateful that you’ve chosen to come along with me this year.

xo

Claire

I enjoyed the piece but I wonder about this line: "This “neural resource allocation problem” may prevent us from ever becoming cyborgs." Here I am thinking about the work of disabled scholars and theorists who identify as cyborgs already (such as Jillian Weise): https://www.wired.com/story/cyborg-brain-mind-pandemic-philosophy/