Those Curious Naturalists

To close the year, a long meander on the dark edges of human-animal cohabitation.

It all started during my lucid dream phase. Hunting for references to lucid dreaming in literature and philosophy, I found someone’s dissertation, which referenced an obscure story by the British writer Lawrence Durrell. I’d never heard of Durrell, but his Alexandria tetralogy of novels sounded interesting: four interleaving accounts of the same story, set in Alexandria, Egypt, in the 1930s.

I read the first, Justine, and from there I was briefly Alexandria-mad: I couldn’t get enough of Rue Rosette and the Grande Corniche, Lake Mareotis, the “Canopic mouth” of the Nile, and the dusky nights Durrell described in shades of mauve. As a chaser, I read the poet C. P. Cavafy, a longtime Alexandrian, and E.M. Forster’s chatty guidebook to the city, where he was stationed as a Red Cross volunteer during WWI.

Having dispatched all of Durrell’s Alexandria books, I eventually found my way to his daughter, Sappho, a playwright who died by suicide at the age of 34. Granta published some of her journals in the early 1990s, in which she makes multiple allusions to childhood sexual abuse. “I want to play around with the idea of parricide—not in general but in specific,” she wrote, in the very first entry. “Vis à vis my father.”

So that was that for my Durrell era. Or so I thought.

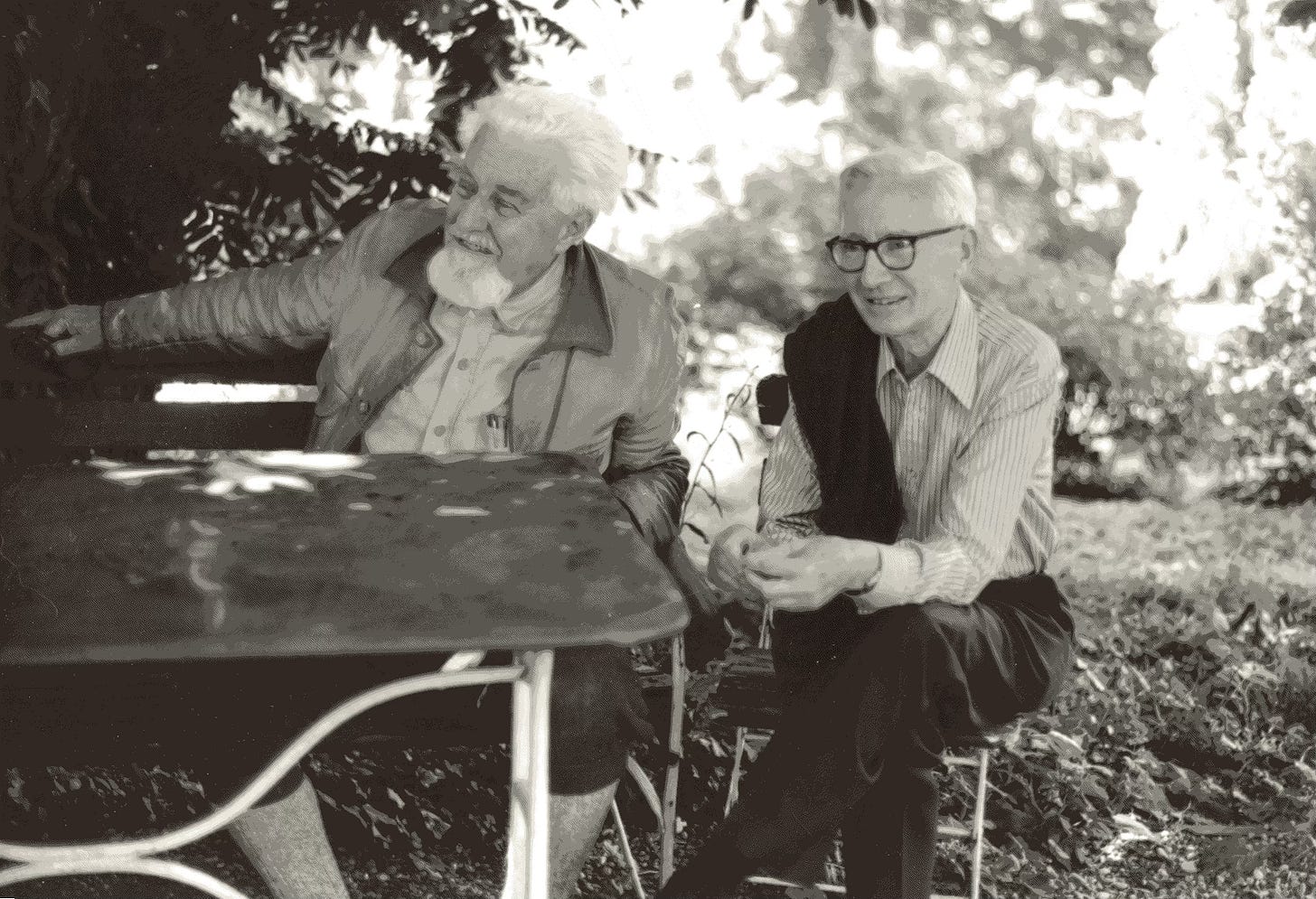

Three weeks later I was in a thrift shop (as ever) and came across an odd little paperback by a Jacquie Durrell, who I learned was the ex-wife of Lawrence’s brother, Gerald, a famous naturalist. Lawrence, as it turned out, was not the most notorious Durrell; Gerald, OBE, wrote bestsellers too, including My Family and Other Animals, an account of his childhood with his bookish brother “Larry” on the island of Corfu.

Gerald’s dream, in those early years, was to own a zoo; in the late 1940s, he made it happen, using his inheritance to mount animal-sourcing expeditions to Britain’s colonial territories in Cameroon and Guyana. He further subsidized his journeys into equatorial Africa by publishing travelogues dramatizing his negotiations with tribal leaders and the madcap bush expeditions it took to fill ships with angwantibos, macaws, and skinks (a large percentage of these animals, injured by the traps set to ensnare them and lacking appropriate care, died on the journey back to England).

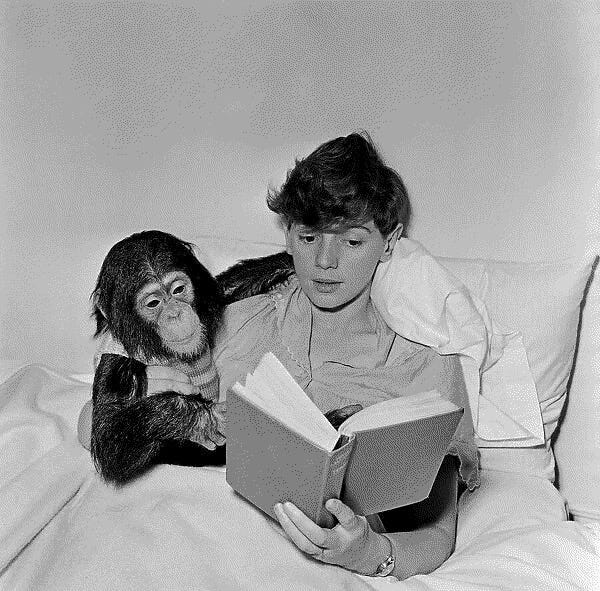

Jacquie’s book, Beasts in my Bed, is something of coda to her husband’s accounts; a wife’s-eye view of the dubious, dusty business of animal-sourcing, complete with patronizing footnotes from Gerald (“women do like to exaggerate” — GD). Back in Bournemouth, they kept the animals at home while they searched for a suitable site for what eventually became the Jersey Zoo. Bush-babies and squirrels cozied together in the garage and Cholmondely, a chimpanzee in diapers, slept in the Durrells’ bedroom, where he swung from the drapes and “learnt to accept light, noise, cigarette smoke and anything else without detriment to his health or well-being.” Okay.

I’ve always been of two minds about zoos. They shouldn’t exist, but there is something about a kid seeing a giraffe with their own eyes, especially now, in our age of illusion, for them to know that such an animal is real and worthy of protection, out there. Maybe, for an animal born in captivity, that’s the best you can hope for. But stealing animals from stolen land, as the Durrells did, is inconceivable. What struck me, reading Beasts in my Bed, was the entitlement. The animals were theirs for the taking. Each in a box, to be fed cut fruit and second-rate steaks for the rest of their days. This was a better life than their birthright. “Contrary to the popular belief,” writes Jacquie Durrell, animals do not “live in a Utopian state where all their whims and fancies are catered for; in fact some of them were in appalling condition when they came to us.”

Slightly more charming, in this genre, are the writings of the Austrian animal ethologist Konrad Lorenz, whose 1959 book King Solomon’s Ring was another thrift store buy for me: a paperback with illustrated marginalia of creatures great and small. Lorenz comes off as more Dr. Doolittle than Dr. Durrell. From his perch on the banks of the Danube, an “island of wilderness in the middle of Lower Austria,” he made his own home a zoo: tame rats darted underfoot throughout the house, nipping “neat little circular pieces” from the linens to pillow their nests, and a gaggle of greylag geese, imprinted on Lorenz as their disproportionate but loving parent, lounged in the flowerbeds by day and the bedroom by night. In this way Lorenz did his most famous work, a study of the birds’ instinctive bonds—by becoming father goose.

The scientific logic for this unorthodox cohabitation was that “captivity cages minds as well as bodies,” and animal behavior is best observed without the intermediation of the cage. Lorenz allowed animals free rein in his house so that he could watch how their minds worried the world—how they solved problems, formed bonds, and overcame, in time, their fear of man. There’s no question he formed deep attachments with these creatures; on hands and knees, in his best approximation of a waddle, he daily led his goslings to water. But something about his writing troubled me, too: a certain incongruity about what it means to be “wild” or “free.” After all, geese running loose in the larder are still captive. Is it such an inconvenience to go to where they live?

The nagging sense I had, reading my thrift-store Lorenz, was that his menagerie of animal roommates were not being understood on their own terms. Peeled off and delaminated from their world, they were instrumentalized in service of something I couldn’t quite place. Narrative, scientific notoriety, or ideology? It didn’t take much research for me to find the answer. Lorenz, although rehabilitated to the point of receiving a Nobel Prize in 1973, had been, before the War, an unguarded supporter of National Socialism, and used his theories about animal behavior to justify Nazi policy.

According to the German historian Ute Dichmann, Lorenz published several papers in the early 1940s arguing that domesticated hybridized geese, cut off from the harsh winnowing of natural selection, were destined to become evolutionary degenerates, and that “cultured peoples,” having attained a certain stage of civilization, were susceptible to the same “physical and moral manifestations of decay.” That is, he believed that interbreeding weakened races just as it dimmed the natural instincts of wild birds. We know where such logic leads; during the War, Lorenz assisted the Nazi psychologist Rudolf Hippius in racial studies on humans in occupied Poland.

Far more competent scholars than me have explored this unsettling subject (Dichmann’s Biologists Under Hitler, in particular, is an enlightening read). I just find it interesting what the keeping of animals can reveal. It isn’t neutral. In the case of the Durrells, for all their later emphasis on conservation, a zoo served as a living index of a violent empire; for Konrad Lorenz, close communion with waterfowl fed a scientific justification for eugenics. In neither instance were animals intentionally mistreated. I think they were even loved. I guess it comes down to why they were loved, and how.

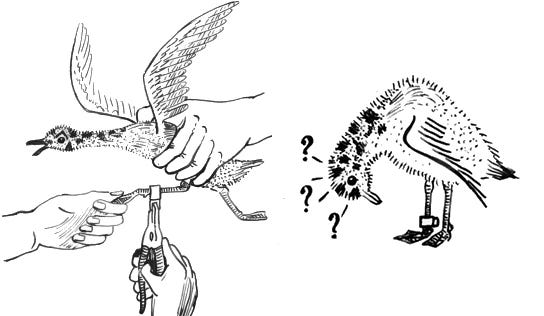

Was it a possessive love, the patriarchal kind? A love born from the misplaced sense that “Man” can do better than “Nature” in making a creature whole? One warped by ideas of hierarchy and racial purity? Ironically, Lorenz shared his Nobel with Niko Tinbergen, an ornithologist who spent two years in a Nazi hostage camp for his role in the Dutch resistance. One of the most striking documents in Dichmann’s book is a letter Tinbergen wrote just after the war to a colleague in the States, accounting for who survived and who was lost. “Many of us have been imprisoned in some way or another,” he wrote. “Our government will demand from everyone a declaration: ‘have you been in prison during the war? If not, why not?’”

By 1945, Tinbergen was eager to get back to his birds. He believed in unfettered observation, in field work. His mantra was “watch and wonder.” Not much time for that during the war. Still, he managed to write a small book about bird sociology, and, while in the camp, some illustrated stories about a Herring gull, which eventually became a beloved children’s book in the Netherlands. What a contrast: Tinbergen imprisoned, dreaming of gulls, the free-flying seabirds of the North Sea. Lorenz walking free, twisting his own observations of birds into a justification for the worst kind of containment and brutality. And later, exploiting their imprinting instinct to form, in the name of science, a twisted patriarchy. To quote Sappho Durrell, on her own father: “I will always have his ego between me and the world, and my surroundings will be as dry as dust.”

Maybe you’re wondering what any of this has to do with technology, or microbiology, or any of the things this newsletter is ostensibly about. Nothing, really, beyond the fact that it’s bracing to chase curiosity, and to honor those weird streaks through books and happenstance where it feels, for a time, like everything is connected. But I do think that these questions of how we regard the living world, and where we stake our vantage over it, are always relevant.

A few weeks ago I had a conversation with a microbiologist who mentioned, in passing, a foundational conflict in his field, the divide between the Koch and Winogradsky models of etiology. Robert Koch, the 19th century biologist whose work provided the basis for the germ theory of disease, saw microbes as immutable pathogens, each tethered in a direct causative relationship with a specific disease. In the lab, he sought to inoculate “pure cultures” free of any “uninvited guests.” Sergei Winogradsky, a Ukrainian ecologist, took a different view: that microbes, like all creatures, lived in variegated and unruly constellations, in nomadic communities rife with competition and collaboration. He preferred to investigate them as closely to their natural habitat as possible, engaged “in the life contest with other microbes.”

Microbiologists still disagree about how best to study their subjects: isolated in a Petri dish, like zoo animals? Or together, as gregarious players in a lively ecology? In 1958, Niko Tinbergen wrote a lovely book, Curious Naturalists, in defense of naturalistic study, his mode of watching and wondering over life. “The biologist has to be aware that he is studying, and temporarily isolating for the purposes of analysis, adaptive systems with very special functions—and not mere bits,” he wrote. These living systems act on us as much as we act on them, and in the case of many microbial communities, they sustain our very existence. In light of this mutual vulnerability, it’s hard to distinguish the animals from their keepers. I’m happy with that.

Finally, a few recommendations for your weekend:

This marvelous primer on Victorian-era acoustics experiments, from the always impressive Public Domain Review. I also really love the Public Domain Image Archive, a bounty of early scientific imagery, Medieval illustrations, and other visual oddities. A collection of 16th century perspective drawings of geometrical figures, with snails and birds included for scale? Yes.

This 1973 John McPhee piece, Travels in Georgia, about two scrappy biologists collecting roadkill, is a straight marvel. James Somers has a few fascinating old blog entries about McPhee’s process; this one, about how he uses the dictionary, originally included a script to install a 1916 edition of Webster’s on your Mac. I’ve never managed to make it work, but maybe you will. I’ll take comfort in my recent discovery that the LA Public Library provides online access to the Oxford English Dictionary; the Historical Thesaurus is a lost weekend waiting to happen.

This 24 hour stream of lo-fi microbes to study to.

I hope everyone who made it this far is enjoying the nub-end of 2025; in these dead days between the holidays and the New Year, may you be accountable to nobody.

xo

Claire

P.S. A bit of news, as a post-script: I’ve been nominated for the Herman Melville Award for Best Writing in a Game by the New York Videogame Critic’s Circle for my work on Blippo+; I’ll be in New York in January for the ceremony. Fingers crossed!

Always enjoy your posts but this one gave me a lot to consider as my great great grandfather was a naturalist. He experienced nature in the same fashion as Tinbergen, going so far as to build a cabin in the Wasatch mountains to categorize and commune as close as possible. I've never considered how if his approach was more clinical, my relationship to nature would be wildly different.

Fascinating look into the other side of long-revered naturalists, but sad in so many ways.